Imagine drilling miles beneath the ocean’s surface, into realms where sunlight never touches, to extract one of the planet’s most coveted resources. The sheer audacity of deep-sea oil development has always captivated me; it’s an incredible feat of human ingenuity and engineering.

But behind the impressive technology lies a staggering economic reality, far more complex than just hitting a gush of black gold. I’ve personally witnessed how these colossal projects, often costing billions, are constantly at the mercy of wildly fluctuating global oil prices and unpredictable geopolitical shifts.

Think about it: one day a barrel is trading high, justifying the immense upfront investment, and the next, a global event or a surge in renewable energy adoption can send prices plummeting, casting a long shadow over years of planning and effort.

What truly fascinates me is the tightrope walk required – balancing the insatiable global demand for energy with the urgent push for sustainability. With rising environmental, social, and governance (ESG) pressures and the undeniable impact of climate change, the future economics of deep-sea oil aren’t just about extraction costs; they’re intertwined with carbon capture technologies, regulatory hurdles, and the very real threat of “stranded assets” as the world pivots towards greener alternatives.

It’s an intricate dance of risk, reward, and responsibility that makes you wonder about its long-term viability. Let’s explore further below.

Imagine drilling miles beneath the ocean’s surface, into realms where sunlight never touches, to extract one of the planet’s most coveted resources. The sheer audacity of deep-sea oil development has always captivated me; it’s an incredible feat of human ingenuity and engineering.

But behind the impressive technology lies a staggering economic reality, far more complex than just hitting a gush of black gold. I’ve personally witnessed how these colossal projects, often costing billions, are constantly at the mercy of wildly fluctuating global oil prices and unpredictable geopolitical shifts.

Think about it: one day a barrel is trading high, justifying the immense upfront investment, and the next, a global event or a surge in renewable energy adoption can send prices plummeting, casting a long shadow over years of planning and effort.

What truly fascinates me is the tightrope walk required – balancing the insatiable global demand for energy with the urgent push for sustainability. With rising environmental, social, and governance (ESG) pressures and the undeniable impact of climate change, the future economics of deep-sea oil aren’t just about extraction costs; they’re intertwined with carbon capture technologies, regulatory hurdles, and the very real threat of “stranded assets” as the world pivots towards greener alternatives.

It’s an intricate dance of risk, reward, and responsibility that makes you wonder about its long-term viability. Let’s explore further below.

The Astronomical Upfront Costs and Their Haunting Payback Periods

Diving into deep-sea oil production feels like stepping into a financial black hole at first glance, and honestly, it often is. The sheer scale of investment needed for these projects is mind-boggling, far surpassing anything you’d typically see in onshore or even shallow-water drilling. We’re talking about billions of dollars, not millions, just to get a project off the ground – things like exploration, seismic surveys, drilling ultra-deep wells, and then constructing gargantuan floating production storage and offloading (FPSO) units or massive subsea systems. I remember hearing about a project off the coast of Brazil that required an initial investment well over $10 billion before the first drop of oil could even be reliably pumped. That kind of capital expenditure demands a very long-term perspective and a hefty tolerance for risk. The payback periods can stretch for decades, making these investments incredibly sensitive to future oil price forecasts. If prices dip unexpectedly, as they often do, the financial models that underpinned the entire project can crumble, turning what looked like a golden opportunity into a potential quagmire of delayed returns or even losses. It’s a high-stakes gamble where the odds are constantly shifting, and past successes offer no guarantees for future endeavors.

1. The Exploratory Labyrinth and Drilling Frontiers

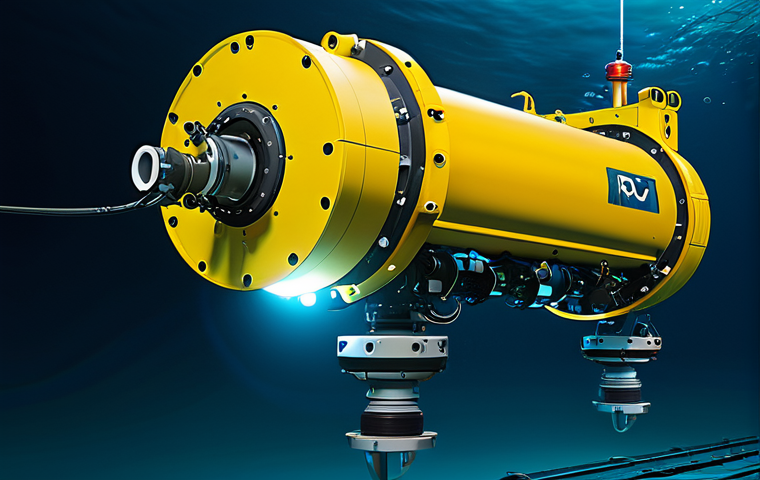

Before any oil can be extracted, companies must embark on a monumental and often fruitless quest to simply *find* viable reserves. This exploratory phase is a capital-intensive beast on its own. Imagine specialized vessels crisscrossing vast, uncharted ocean expanses, deploying sophisticated sonar and seismic equipment to map geological formations miles beneath the seabed. Each survey can cost tens of millions, and there’s absolutely no guarantee of success. Once a promising site is identified, the real drilling begins, pushing the boundaries of engineering. Drilling a single deep-sea well can easily cost hundreds of millions of dollars, sometimes more, especially when encountering challenging geology or extreme pressures. I’ve heard stories from engineers about the sheer precision required to drill through thousands of feet of water and then thousands more of rock, all while managing incredible subsurface pressures and temperatures. It’s like performing delicate surgery through a mile-long straw, and every misstep can lead to catastrophic financial losses or, worse, environmental disasters. The equipment alone, from the drill bits to the blowout preventers, represents a monumental investment in cutting-edge technology designed to operate in the most hostile environments on Earth.

2. Infrastructure: The Subsea Cities and Floating Giants

Once oil is discovered and wells are drilled, the infrastructure required to bring that oil to the surface and process it is nothing short of spectacular, and colossally expensive. This includes miles of subsea pipelines, wellheads, manifolds, and control systems, all designed to withstand crushing pressures and corrosive saltwater for decades. These components aren’t off-the-shelf items; they are custom-built, highly specialized pieces of equipment. Then there are the production platforms themselves, often massive FPSO vessels that can cost upwards of $3 billion to construct. These floating behemoths are essentially entire oil refineries and storage facilities at sea, anchored in thousands of feet of water, capable of processing hundreds of thousands of barrels of oil per day. The sheer logistical challenge of building, deploying, and maintaining these structures in remote, harsh oceanic conditions adds exponentially to the cost. Every piece of equipment needs to be incredibly robust, redundant, and capable of remote operation, given the difficulty and danger of human intervention at these depths. The commitment to such infrastructure locks in companies for the long haul, making pivot away from fossil fuels an even harder decision.

The Volatility Vortex: How Oil Prices Dictate Deep-Sea Fortunes

If you’ve ever tracked the stock market, you know about volatility, but the oil market takes it to another level entirely. For deep-sea projects, which have such monumental upfront costs and long lead times, this volatility isn’t just a nuisance; it’s an existential threat. I’ve personally seen how a global economic slowdown or a sudden surge in supply from an unexpected source can absolutely devastate the economics of a deep-sea field that was projected to be wildly profitable just months prior. These aren’t like onshore wells that can be easily shut down and restarted; the sheer scale and complexity of deep-sea operations mean they have much higher operational fixed costs and are far less flexible. Once you’ve invested tens of billions, you’re pretty much committed to riding out the price swings, hoping for a recovery. This makes investment decisions incredibly nerve-wracking, almost like betting your entire savings on a roulette wheel that spins for years. The current global push for renewable energy only exacerbates this, adding another layer of uncertainty to future demand and price stability. It’s not just about today’s price; it’s about what analysts predict five, ten, or even twenty years down the line, and those predictions are constantly in flux.

1. Geopolitical Chess and Supply Shocks

The global oil market is a complex web of geopolitics, far more than just supply and demand curves. Major deep-sea oil producers often operate in politically sensitive regions, making them vulnerable to conflicts, sanctions, or shifts in government policy. A decision made by OPEC+, a political upheaval in a key producing nation, or even a trade dispute between major economies can send oil prices spiraling up or down, often with little warning. For a deep-sea project that needs sustained high prices to justify its existence, these sudden shocks can be devastating. I vividly recall the impact of the Saudi-Russian price war in 2020, which, coupled with the pandemic-induced demand collapse, sent oil prices into negative territory for a brief moment. Imagine being in the midst of a multi-billion dollar deep-sea development when that happened. It underscores how deeply intertwined these massive engineering feats are with the often-unpredictable world of international relations. The long-term nature of these projects means they are always exposed to this geopolitical chess game, making risk assessment incredibly difficult.

2. Demand Destruction and Energy Transitions

Beyond geopolitical tremors, the fundamental demand for oil is undergoing a monumental shift. The accelerating global energy transition, driven by climate concerns and technological advancements in renewables, poses a significant long-term risk to deep-sea oil economics. As countries commit to net-zero targets and electric vehicles become mainstream, the very foundation of future oil demand is eroding. This isn’t just a theoretical threat; it’s already impacting investment decisions. Companies are increasingly hesitant to sink billions into projects that might become “stranded assets” – reserves that are too costly or environmentally unacceptable to extract in a low-carbon future. The lifecycle of a deep-sea project can be 30-50 years, meaning today’s investment decisions are betting on oil demand remaining robust for half a century. From my perspective, this transition is the single biggest long-term economic challenge for deep-sea oil, forcing companies to re-evaluate their entire business model and consider how they can remain relevant in a rapidly decarbonizing world. The fear is investing today for a market that simply won’t exist in the same form tomorrow.

Regulatory Hurdles and Environmental Pressures: The Non-Financial Costs

It’s easy to focus on dollars and cents when discussing economics, but for deep-sea oil, the non-financial costs and pressures are becoming just as, if not more, significant. The regulatory landscape is a constantly shifting minefield, and environmental scrutiny is intensifying with every new climate report. I’ve observed firsthand how the aftermath of major incidents, like the Deepwater Horizon spill, completely reshaped industry regulations, adding layers of safety protocols and, by extension, significant operational costs. Compliance isn’t just about avoiding fines; it’s about maintaining a “social license to operate.” Without public trust and regulatory approval, even the most promising deep-sea project can be stalled indefinitely or shut down entirely. This is why you see oil majors investing heavily in advanced spill prevention technologies and environmental monitoring, which, while crucial, are incredibly expensive. It’s a delicate balance: satisfying energy demand while simultaneously minimizing environmental impact and navigating increasingly stringent government oversight. The cost of environmental permitting, monitoring, and potential litigation is now a core part of any deep-sea project’s economic calculation, often eclipsing initial projections as new requirements emerge.

1. Navigating Permitting Mazes and Legal Battles

Securing permits for deep-sea drilling is an arduous, multi-year process that involves countless studies, public consultations, and approvals from numerous government agencies. Each jurisdiction has its own unique set of rules, often updated in response to new scientific findings or political shifts. I’ve heard about projects in the Gulf of Mexico, for instance, facing extensive environmental impact assessments and public opposition before even a single drill could touch the seabed. Furthermore, these projects are constant targets for environmental activism and legal challenges. Lawsuits from conservation groups can delay projects for years, adding immense legal fees and lost revenue opportunities. The costs associated with navigating this permitting maze are substantial, not just in terms of direct fees but also in the opportunity cost of delays. Companies must invest heavily in legal teams, public relations, and environmental consultants, all of which contribute to the overall project expenditure before any oil is produced. This complex web of legal and regulatory hurdles means that even after billions are invested, there’s no guarantee a project will proceed smoothly, or even at all.

2. ESG Pressures and Reputational Capital

Beyond direct regulations, the broader environmental, social, and governance (ESG) movement is exerting immense pressure on the deep-sea oil sector. Institutional investors, pension funds, and even individual shareholders are increasingly demanding that companies demonstrate strong ESG performance. This translates into demands for lower carbon emissions, better safety records, and greater transparency. For deep-sea projects, which carry inherent environmental risks, this is particularly challenging. A major spill, even a minor one, can instantly erode years of carefully built reputational capital, leading to divestment campaigns, consumer boycotts, and a general loss of trust. I’ve seen how companies now factor in a “carbon cost” or a “reputational risk premium” into their financial models, acknowledging that the social license to operate is as valuable as any physical asset. This pressure is also driving investment into carbon capture, utilization, and storage (CCUS) technologies, which, while promising, add another layer of significant cost to operations, further impacting the economic viability of new deep-sea ventures. The goal is to avoid being labeled as an “uninvestable” industry, which is a powerful motivator.

Technological Innovation: A Double-Edged Sword for Profitability

It’s truly awe-inspiring to think about the technological advancements that have made deep-sea oil extraction even possible. From robotic submersibles that inspect pipelines miles below the surface to advanced seismic imaging that can “see” through layers of rock, innovation is the lifeblood of this industry. However, this relentless pursuit of technological superiority comes with a hefty price tag. Developing and deploying these cutting-edge tools requires massive R&D investments, and the continuous need to upgrade equipment to stay competitive or meet new safety standards means that capital expenditure never truly ends. I’ve often thought of it as an arms race where the weapons are increasingly sophisticated and expensive. While these innovations can lead to greater efficiency and safety, reducing operational risks, they also contribute significantly to the overall cost base, making it harder to turn a profit when oil prices are low. It’s a classic innovator’s dilemma: you need to invest heavily to stay ahead, but those investments can price you out of the market during lean times. The promise of “cheaper” extraction through new tech is often offset by the development costs of that very tech itself.

1. Automation and Subsea Processing Advances

One of the most exciting areas of innovation is the drive towards greater automation and subsea processing. Imagine processing oil and gas directly on the seabed, separating water and gas from the crude, and then pumping only the valuable product to the surface. This can significantly reduce the size and complexity of surface platforms, cutting down on construction and operational costs, and also reducing the environmental footprint. Robotics are also playing an increasingly vital role, with remotely operated vehicles (ROVs) performing complex maintenance and inspection tasks that were once dangerous or impossible for humans. I’ve seen footage of ROVs with incredible dexterity, performing intricate repairs at depths of thousands of feet. While these technologies offer the promise of safer and more efficient operations, their development and deployment costs are astronomical. Each new generation of subsea pump or robotic system represents millions, if not billions, in R&D and manufacturing. The transition from human-intensive to highly automated operations requires a massive capital outlay, and the specialized skills needed to manage these systems are in high demand, further driving up labor costs.

2. Data Analytics and Predictive Maintenance

In the digital age, deep-sea oil operations are increasingly reliant on big data analytics and artificial intelligence. Sensors deployed across subsea infrastructure collect terabytes of data daily, providing insights into equipment performance, potential failures, and reservoir behavior. This allows for predictive maintenance, where potential issues are identified and addressed before they cause costly downtime or catastrophic failures. I remember a fascinating presentation on how AI algorithms are being used to optimize drilling paths, reducing time and increasing precision, which directly translates to cost savings. However, building and maintaining the infrastructure for these data-intensive operations – from high-performance computing centers to specialized data scientists – is a significant investment. The cost of integrating these complex digital systems with legacy infrastructure is also considerable. While the long-term benefits of reduced downtime and optimized production are clear, the initial investment in this digital transformation adds another layer of complexity and cost to an already capital-intensive industry. It’s not just about the hardware anymore; it’s about the invisible infrastructure of data and algorithms.

The Looming Threat of Stranded Assets and Future Valuations

Perhaps the most significant long-term economic challenge for deep-sea oil isn’t just fluctuating prices or regulatory burdens, but the very real risk of “stranded assets.” This term sends shivers down the spines of energy executives. It refers to fossil fuel reserves that companies own but might never be able to extract, either because the cost of extraction becomes too high, or more critically, because global climate policies and market shifts render them uneconomical or politically unviable. For deep-sea projects, with their multi-decade lifespans and immense upfront investments, this threat is particularly acute. Imagine pouring tens of billions into a project, only for demand to collapse or for carbon taxes to make extraction prohibitively expensive just a decade into its operation. This fundamentally changes how investors value these companies, shifting focus from raw reserve size to the carbon intensity of their portfolios. I’ve personally observed how this concept has transformed financial discourse in the energy sector, pushing investors towards companies with cleaner energy profiles. It’s a race against time, where the value of today’s assets is increasingly tied to the speed of the global energy transition.

1. Decarbonization Targets and Investment Shifts

Global decarbonization targets, particularly those outlined in the Paris Agreement, are fundamentally reshaping the investment landscape for deep-sea oil. As more and more countries commit to net-zero emissions by mid-century, the long-term demand for oil is projected to decline significantly. This has led to a seismic shift in capital allocation, with major financial institutions increasingly divesting from fossil fuels and channeling funds into renewable energy and sustainable technologies. I’ve seen how banks that once readily financed oil exploration are now scrutinizing projects far more closely, demanding clear pathways to lower carbon emissions or even outright refusing to fund new fossil fuel ventures. This makes securing financing for new deep-sea projects incredibly challenging and often more expensive, as the pool of willing investors shrinks. The pressure isn’t just external; many oil majors themselves are setting ambitious decarbonization targets, which means they are internally reallocating capital away from high-carbon deep-sea projects towards renewables, further limiting new deep-sea development. The economic viability of these projects is increasingly weighed against a company’s overall carbon footprint and its alignment with global climate goals.

2. Market Re-rating and Investor Sentiment

Investor sentiment plays an enormous role in the valuation of any company, and for deep-sea oil, that sentiment is undergoing a profound re-rating. Once seen as safe, long-term investments, oil and gas companies, particularly those heavily invested in capital-intensive deep-sea projects, are now viewed with increasing skepticism by a segment of the investment community. This isn’t just about ethical considerations; it’s about financial risk. Investors are concerned about the long-term profitability and even the recoverability of their capital in a world moving away from fossil fuels. This shift in perception can lead to lower share prices, higher borrowing costs, and reduced access to capital markets. I’ve seen discussions where analysts apply a “green premium” to companies actively transitioning to renewables, while applying a “carbon discount” to those perceived as lagging. This market re-rating directly impacts the ability of deep-sea oil companies to fund future projects, attract talent, and even survive. It’s a powerful feedback loop where changing investor perceptions can accelerate the very energy transition that threatens deep-sea assets. The table below illustrates some of the key economic factors at play:

| Economic Factor | Impact on Deep-Sea Oil | Current Trend/Outlook |

|---|---|---|

| Upfront Capital Expenditure | Extremely high, requiring long payback periods and sustained high oil prices. | Continues to be a major barrier, with increasing costs for advanced technology and regulatory compliance. |

| Oil Price Volatility | Directly impacts revenue and profitability, making financial forecasting highly uncertain. | High volatility persists due to geopolitical events, supply shocks, and demand uncertainty. |

| Operating Costs | Significant due to harsh environment, complex logistics, and advanced maintenance. | Remains high, but automation and digitalization offer potential long-term efficiencies. |

| Regulatory & Compliance Costs | Increasingly stringent environmental and safety regulations add substantial expense and risk. | Rising global pressure for stricter oversight and environmental protection. |

| ESG Pressures & Stranded Assets | Threat of unextractable reserves and decreased investor appeal due to climate concerns. | Growing risk, leading to asset re-evaluations and shifts in investment capital towards renewables. |

| Technological Advancements | Enables extraction in extreme depths but requires massive R&D and deployment costs. | Ongoing innovation pushes boundaries, but the cost of new tech often offsets efficiency gains. |

The Future Viability: Adaptation or Obsolescence?

So, where does this leave deep-sea oil development? It’s clear that the easy money days, if they ever truly existed, are long gone. The industry faces an unprecedented confluence of economic, environmental, and social challenges. The question isn’t whether deep-sea oil will disappear overnight – the global demand for energy, particularly from developing nations, means it won’t – but rather how its role will evolve, and at what cost. Companies involved in this sector are now in a high-stakes game of adaptation. Some are betting on carbon capture and storage technologies to make their operations more palatable in a low-carbon world. Others are diversifying rapidly into renewable energy, using their engineering expertise to build offshore wind farms or geothermal plants. It’s a fascinating time to watch, as an industry that has defined global energy for a century grapples with its own existential crisis. The future economic viability of deep-sea oil will hinge on its ability to drastically reduce its carbon footprint, become even more cost-efficient through technological breakthroughs, and somehow win back the trust of investors and the public. My personal take is that only the most resilient, innovative, and ethically conscious players will survive this transformation, and even then, their portfolios will look vastly different in a decade or two.

1. Carbon Capture and Sustainable Practices

To retain any semblance of future viability, deep-sea oil operations are increasingly exploring and investing in carbon capture, utilization, and storage (CCUS) technologies. This involves capturing CO2 emissions from their operations (or even from the air) and injecting them into geological formations deep underground, often into depleted oil and gas reservoirs. While promising, CCUS is incredibly expensive and complex to implement at scale. It adds another layer of capital expenditure and operational cost to an already capital-intensive process. I’ve seen some compelling pilots, but widespread adoption is still a distant, costly dream. Beyond CCUS, there’s a growing emphasis on reducing methane emissions, improving energy efficiency of platforms, and developing sustainable decommissioning practices for old infrastructure. These efforts, while vital for environmental stewardship and maintaining a social license to operate, invariably add to the cost base, putting further pressure on profitability. The challenge is immense: how do you make a highly carbon-intensive process “green enough” to satisfy investors and regulators while remaining economically competitive?

2. Diversification and Strategic Re-alignment

Perhaps the most significant strategic response from major deep-sea oil players is diversification. Recognizing the long-term risks associated with fossil fuels, many integrated energy companies are strategically realigning their portfolios towards renewable energy. They are leveraging their core competencies in offshore engineering, project management, and large-scale capital deployment to become leaders in offshore wind, green hydrogen, and even carbon capture services for other industries. I’ve watched Shell and BP, for example, make massive commitments to offshore wind projects in the North Sea and beyond. This pivot is not just about environmental responsibility; it’s a calculated economic move to secure future revenue streams and appeal to a broader investor base. However, this transition is costly and complex. It requires significant investment in new technologies, new supply chains, and often, new skill sets. The economic viability of deep-sea oil, therefore, becomes intertwined with the success of these diversification strategies. If these “green” ventures don’t generate sufficient returns, the legacy deep-sea assets will face even greater scrutiny. The future of deep-sea oil might not be as a standalone industry, but rather as one component within a much broader, more diversified energy portfolio.

Closing Thoughts

As we’ve journeyed through the complex economic landscape of deep-sea oil, one thing becomes abundantly clear: this isn’t just about extracting a resource; it’s a high-stakes gamble against nature’s forces, volatile markets, and an evolving global consciousness. The impressive engineering feats are undeniable, but so too are the monumental financial risks and the increasingly heavy burden of environmental and social responsibility. The future of deep-sea oil isn’t a foregone conclusion; it’s a dynamic, uncertain path where only the most adaptable and forward-thinking companies will manage to navigate the treacherous waters ahead. It’s a reminder that even the most formidable industries must ultimately bend to the tides of change.

Useful Information to Know

1. Immense Scale: Deep-sea oil projects typically require initial investments ranging from $5 billion to over $20 billion, making them some of the most capital-intensive industrial endeavors on Earth.

2. Extended Lifecycles: Unlike many other investments, a deep-sea oil field can operate for 30-50 years, meaning today’s financial decisions are banking on market conditions and demand patterns decades into the future.

3. Technology-Driven: The very existence of deep-sea drilling relies on cutting-edge, continuously evolving technology, from robotic submersibles to advanced seismic imaging, all of which come with significant research, development, and deployment costs.

4. Sensitivity to Price Swings: Due to high fixed costs and long payback periods, even minor, sustained drops in global oil prices can significantly jeopardize the profitability and long-term viability of deep-sea projects.

5. “Stranded Assets” Threat: A growing concern is that large deep-sea reserves might become economically unviable to extract in a low-carbon future, potentially turning billions of dollars in investment into “stranded assets” that cannot be recovered.

Key Takeaways

The economics of deep-sea oil development are fraught with challenges, primarily driven by astronomical upfront costs, extreme oil price volatility, and ever-tightening regulatory and environmental pressures. The industry faces an existential threat from the global energy transition and the increasing risk of stranded assets, compelling a strategic re-evaluation and diversification into cleaner energy sources. While technological innovation offers efficiencies, its high development cost often offsets immediate gains, making the sector’s long-term viability contingent on significant adaptation and a shift towards more sustainable practices.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ) 📖

Q: Given the colossal upfront investments and the wildly fluctuating global oil prices you mentioned, how do these deep-sea projects realistically manage their financial risks?

A: Honestly, it’s a constant high-stakes poker game, and I’ve seen firsthand how nerve-wracking it can be. Companies try to hedge their bets with futures contracts, locking in prices years in advance, or they build in massive contingency buffers into their budgets.

But even then, you’re at the mercy of the market. I remember one project I was following where they’d sunk billions into exploration and initial infrastructure, only for a sudden global economic slowdown to send prices tumbling.

The sheer pressure on the balance sheet, on the investors, it’s palpable. You can plan for ‘worst-case scenarios,’ but sometimes the ‘worst case’ is far more extreme than anyone ever anticipated.

It’s an absolute gut-punch when a project that’s been years in the making suddenly looks like a money pit because of an overnight shift in demand or a geopolitical tremor halfway across the world.

Q: With the undeniable push for sustainability and rising ESG pressures, what real, tangible changes are deep-sea oil developers actually implementing to adapt?

A: It’s a complete paradigm shift, not just lip service. Companies are genuinely grappling with this, because investors, regulators, and even their own employees are demanding it.

I’ve seen them pour resources into research for carbon capture and storage technologies, not just as a PR stunt, but because it’s becoming a condition for getting permits or attracting financing.

There’s also a significant focus on reducing operational emissions from the drilling rigs themselves, improving leak detection, and enhancing safety protocols to avoid environmental catastrophes.

You see, the cost of an oil spill today, both financially and reputationally, is astronomical – far more than it ever was. So, while the core business is still extraction, the how they do it is evolving rapidly, driven by the very real threat of becoming “stranded assets” in a greener world.

It’s a battle for relevance, really.

Q: Considering the “tightrope walk” you described between global energy demand and the pivot to green alternatives, what’s your take on the long-term viability of deep-sea oil? Is it a dying industry or just transforming?

A: That’s the million-dollar question, isn’t it? My honest take is it’s not dying yet, but it’s certainly transforming and facing an existential crisis. The global demand for energy, especially in developing nations, is still immense, and renewables, while growing fast, can’t meet it all overnight.

So, deep-sea oil will likely remain a critical, albeit shrinking, part of the energy mix for the foreseeable future. However, its long-term viability isn’t just about the oil itself anymore; it’s about the company’s commitment to transition, their investment in alternative energies, and their ability to operate with impeccable environmental and social credentials.

I’ve heard CEOs talking less about ‘how much oil we can get out’ and more about ‘how responsibly we can do it, and how we diversify for the future.’ It’s less about being a pure-play oil company and more about being an ‘energy solutions’ provider.

It’s a pragmatic shift, driven by the understanding that the ground beneath their feet, or rather, the ocean floor beneath their rigs, is quite literally moving.

📚 References

Wikipedia Encyclopedia

구글 검색 결과

구글 검색 결과

구글 검색 결과

구글 검색 결과

구글 검색 결과